A Brief History of Trauma: From Wounds and Wars to a Word That Shapes How We Heal

From battlefield shell shock to TikTok hashtags, trauma has travelled far. I trace its evolution - and why our future understanding must be precise.

The word trauma has slipped its clinical leash. Once confined to psychiatrists' offices and academic journals, it now bleeds into everyday speech. We talk about "traumatic" breakups, "traumatic" jobs, "traumatic" politics.

From memoirs to TikTok, from therapy rooms to Twitter threads, trauma is everywhere - a lens through which people narrate identity, suffering, even resilience. It’s even been called the ‘word of the decade’.

There's power in this diffusion. To name a wound is to dignify it, to insist it matters. The language of trauma has helped survivors of war, abuse, and neglect move from silence to recognition.

Today's newsletter is sponsored by The Trauma Training Institute.

Discover how they're helping mental health practitioners learn to work with developmental trauma.

But ubiquity carries a risk: if everything is trauma, then nothing is. When nuance erodes, the concept blunts. The danger is not only semantic but practical - it shapes how therapists intervene, how communities respond, how people make sense of pain.

But how did we get here? How did a medical term become something we use to describe anything we find difficult or uncomfortable? That’s what this week’s Brink is going to find out.

And I’m doing that with the help of my first newsletter sponsor! The amazing Trauma Training Institute. More on them later.

From Wounds to Words

The word trauma begins simply. In classical Greek, traûma meant a wound - the tear of flesh, the puncture of skin, the mark of violence on the body. Homer used it for the gashes left by spears and arrows; Hippocratic texts catalogued traumata as physical injuries requiring surgical intervention. It was a matter of blood and bone, not memory or psyche.

Latin medicine carried the word forward. By the Renaissance and early modern era, trauma appeared in anatomical and surgical treatises as shorthand for bodily injury. Surgeons' manuals of the 16th and 17th centuries used the term to classify everything from battlefield lacerations to domestic accidents. The meaning was literal: to be traumatised was to be torn, cut, or broken in visible ways.

By the 18th and early 19th centuries, the word had seeped into wider use. Metaphor crept in: writers spoke of "social trauma" or "political trauma" to evoke the scars left by revolutions, wars, or upheaval. Still, the centre of gravity was physical injury.

The shift began with the industrial age. Railways, factories, and war machines brought accidents of unprecedented scale, and doctors noticed something unsettling: patients whose bodies bore no obvious wound yet remained plagued by tremors, nightmares, paralysis. Physicians used the old word - trauma - but stretched it to describe an invisible wound, a break not in flesh but in the nervous system, in the mind itself.

In that moment, trauma became more than surgical vocabulary. It became a metaphor for the unseen, the unhealed, the unspoken. A single syllable carrying both the wound, and the world that caused it.

Railways, nerves, and the birth of psychological trauma

The industrial age created new kinds of wounds. In Britain and across Europe, the speed and violence of railway travel brought accidents of a scale never seen before. Passengers walked away from crashes without a scratch, only to collapse days or weeks later with tremors, paralysis, nightmares, memory loss. Doctors labelled it "railway spine" - a disorder thought at first to be a microscopic injury to the spinal cord, but increasingly recognised as something less tangible, more elusive.

The term caught fire in medico-legal debates. Could invisible injuries really disable a man? Was it fraud, malingering, or proof that experience alone could shatter the nervous system? Lawsuits against railway companies made doctors scrutinise these cases in unprecedented detail, edging medicine toward a recognition that trauma might be psychological as well as physical.

In Paris, neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot was conducting his own investigations into hysteria at the Salpêtrière hospital. He demonstrated that traumatic memories could be revived under hypnosis, producing convulsions, paralysis, even blindness with no organic lesions. His student Pierre Janet (one of the founding fathers of psychology) extended these insights. In L'automatisme psychologique and L'état mental des hystériques, Janet described dissociation: the splitting of memory and consciousness when events overwhelm the psyche.

Meanwhile in Vienna, a young Sigmund Freud absorbed these ideas. His early work with Austrian doctor Josef Breuer on Studies on Hysteria proposed that repressed memories of trauma, when expressed in words, could bring relief - the beginnings of the "talking cure".

The late 19th century marked a profound pivot in how we thought about wounds. Trauma moved from the battlefield and the surgeon's knife to the railway carriage, the courtroom, the clinic. For the first time, doctors conceded that a wound could be real even if the body appeared unmarked. But that tension will never truly leave trauma. As we’ll find later on.

Shell Shock and the Soldiers Who Shook History

If the railways introduced trauma to the courtroom, the trenches forced it onto the world stage. World War I produced millions of men who returned home broken in ways no X-ray could show. They shook uncontrollably, stammered, froze mid-sentence, and woke screaming from dreams of shellfire. The name was blunt: shell shock.

At first, it was dismissed as cowardice. Some officers insisted it was mere malingering - an excuse to escape combat. Soldiers who faltered were labelled weak, even court-martialled. More than 300 British servicemen were executed during the war, many of them likely suffering from psychological collapse rather than criminal intent.

But the scale of suffering made denial impossible. Medical officers documented men trembling so violently they could not hold a cup, veterans who flinched at every sound, soldiers struck mute without any physical injury.

In one account from Craiglockhart War Hospital in Edinburgh, a young officer "stood at attention, but the moment a door slammed, he crumpled to the ground as if felled by a shell." The war poets Siegfried Sassoon and Wilfred Owen both passed through Craiglockhart, writing of men "who crouched in dug-outs, staring dumb with terror."

The debates raged: was shell shock neurological, psychological, or moral? Some physicians looked for microscopic brain damage; others argued it was the mind's reaction to unendurable horror. Whatever the cause, the effects lingered long after the guns fell silent.

By World War II, understanding had deepened. In 1941, the American psychiatrist Abram Kardiner published The Traumatic Neuroses of War, mapping how nightmares, hypervigilance, and social withdrawal endured for years. Trauma, he showed, was not a temporary nervous collapse but a chronic condition - the battlefield echoing in civilian life.

The trenches forced a cultural reckoning: wounds of the mind could no longer be dismissed as cowardice. Trauma had entered medicine - and the modern imagination.

From Vietnam to the DSM: Naming PTSD

The Second World War forced psychiatry to confront trauma on a scale even greater than the trenches of 1914. Beyond soldiers, entire civilian populations were scarred: the Blitz in London, the firebombing of Dresden, the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Yet it was the survivors of the Holocaust who most clearly revealed that trauma was not simply about immediate shock but about enduring psychic rupture. Psychologists like Bruno Bettelheim and later Dori Laub and Judith Herman documented how memory, identity, and meaning itself were fractured by atrocity.

By the 1960s, a new wave of voices made trauma impossible to ignore. Vietnam veterans returned home to a society unwilling to hear their stories. They organised, testified before Congress, and demanded recognition that their nightmares, rage, and isolation were not weakness but injury.

Feminist scholars and activists in the same era reframed rape, domestic violence, and incest not as private shame but as systemic trauma. The civil rights movement and decolonisation struggles brought collective and intergenerational trauma into view.

These converging forces shaped psychiatry's eventual response. When the DSM-III codified Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder in 1980, it did so under pressure from soldiers, survivors, and activists alike. Trauma was no longer confined to the battlefield - it was recognised as the psychic residue of war, genocide, oppression, and violation.

From Holocaust Testimonies to Social Movements

With PTSD officially named in 1980, trauma entered not just the clinic but the culture. What began as a diagnosis for veterans and survivors of atrocity widened rapidly. Child protection movements drew on trauma language to insist that neglect and abuse were not private matters but public health crises. By the 1990s, trauma was a word that signalled seriousness, urgency, legitimacy.

Then came its cultural afterlife. By the early 2000s, trauma was everywhere - a leitmotif in memoirs, novels, and films; shorthand in political commentary; hashtags and captions on social media. The DSM-5, released in 2013, reflected this proliferation, carving out an entire category, Trauma- and Stressor-Related Disorders, broadening the concept further still.

But with all this recognition, something changed. Trauma began to flatten. Online, it became a catch-all for bad bosses, breakups, the grind of everyday life. In some circles it became identity itself: to be traumatised was to be authentic, to belong to a community of the wounded. Critics like Bessel van der Kolk (he of The Body Keeps the Score fame) warned that when trauma becomes your defining feature, it compresses complexity into a single narrative.

And here history loops back. In the late 19th century, doctors argued bitterly over "railway spine": was it fraud, neurosis, or genuine injury? In the First World War, shell shock was branded cowardice before being recognised as suffering.

Once again, trauma is contested - not over whether it exists, but over whether it now explains too much. The danger is different but familiar: when trauma is stretched to cover everything, it risks losing the sharpness that once made it revolutionary.

For therapists, the broad use of the word "trauma" presents a clinical paradox. Clients often arrive naming trauma as the root of their suffering, but the symptoms they bring: chronic self-doubt, mistrust, broken relationship patterns don't always match what we classically associate with trauma.

Yet these are, in fact, hallmarks of relational or developmental trauma - what some modalities, like NARM (NeuroAffective Relational Model), identify as survival strategies.

These patterns emerge not from singular catastrophic events, but from the slow, painful erosion of connection during key developmental stages. When a child's needs for attunement and emotional safety go unmet, the psyche often adapts by disconnecting: from pain, from others, from the self.

The rage or grief that might naturally arise is suppressed in fear of losing the very attachments the child depends on. Instead, children internalize blame, making themselves wrong-believing they deserve the disconnection.

Over time, these adaptations calcify into shame-based strategies like emotional numbing, hyper-independence, or an ingrained belief that one's needs are a burden. As one clinician put it to me, "Everyone comes in with trauma now, but sometimes what they mean is shame, or fear, or loneliness." And often, those aren't separate: they are the trauma.

Researchers and practitioners have responded by developing more precise language - differentiating between shock trauma, developmental trauma, and attachment wounding - to better understand what's truly unfolding in the consulting room. While these terms are sometimes used interchangeably, there are important distinctions.

Developmental trauma - also known as relational trauma - refers specifically to early life experiences, when the child's sense of self is forming and their emotional survival is inextricably tied to the availability and attunement of caregivers. These early wounds create a deep fear of attachment loss, which can lead to shame-based survival strategies that persist into adulthood.

Attachment wounds, on the other hand, can occur later in life - through betrayals, abandonments, or relational ruptures - but the impact often depends on one's early emotional foundation. For those who experienced consistent attunement and safety in childhood, later wounds, while painful, may not trigger the same collapse into chronic self-blame, numbing, or compulsive coping mechanisms.

But for others, these later experiences can echo earlier injuries, reinforcing entrenched patterns of shame, disconnection, and self-abandonment.

Shock vs. Developmental Trauma: Naming the Difference

The push for precision has brought one crucial distinction into focus: the difference between shock trauma and developmental trauma.

- Shock trauma is what we most readily picture when we hear PTSD - a catastrophic event that ruptures life in an instant: a battlefield, a car crash, an assault. The psyche is overwhelmed by a single, overwhelming moment.

- Developmental or relational trauma, by contrast, unfolds slowly. It is the absence of attunement, the drip-feed of neglect, the wound of not being seen or held. It is the child who grows up with an alcoholic parent, or in a home where emotions are dismissed, or in an environment where love feels conditional. No single event may look catastrophic, yet the nervous system is quietly shaped by chronic stress, shame, and disconnection.

For years, these experiences went unnamed. Clients would present with chronic anxiety, self-sabotage, or an inability to form secure relationships, yet without the "big event" that fitted PTSD criteria. That gap began to close with the landmark Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs) study in the mid-1990s.

The findings were stark: the more adverse experiences in childhood - from abuse to household instability - the higher the likelihood of depression, addiction, cardiovascular disease, even shortened life expectancy. Trauma was not just about the extraordinary; it was woven into the ordinary fabric of childhood for millions.

This recognition changed the landscape. It helped therapists name what they were seeing in the consulting room: not post-traumatic stress in the narrow sense, but the long shadow of developmental wounds. Naming is not pedantry - it is precision. Without it, shock trauma and developmental trauma collapse into the same word, obscuring what each actually needs in treatment.

If you’re reading this - either as a practitioner or someone who resonates with these more sophisticated definitions - you might be wondering what tools are available? The next section, and sponsor of this week’s newsletter should help.

Why Nuanced Frameworks Matter

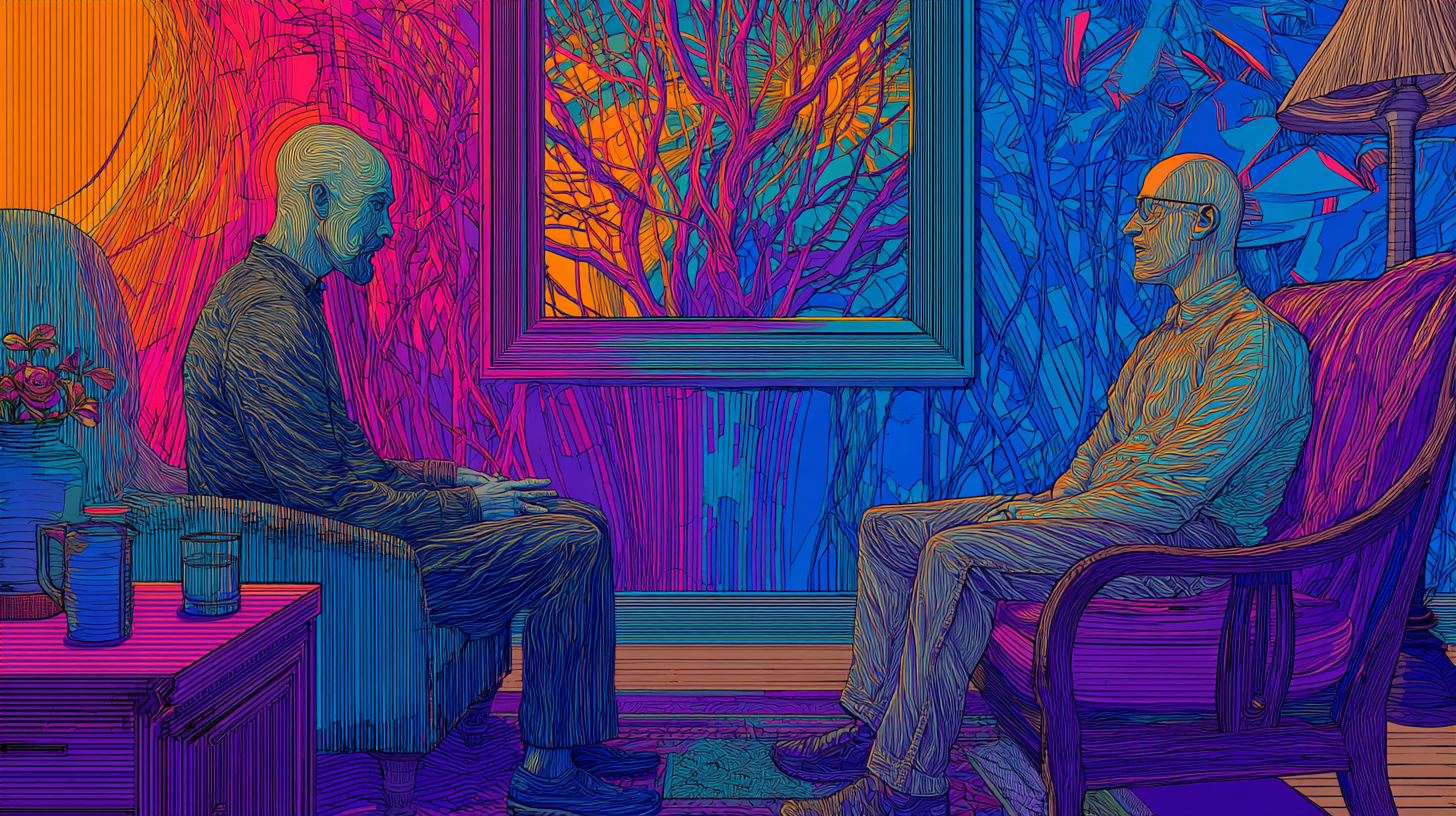

If naming is about precision, practice requires it too. Therapists can't work effectively when every difficulty arrives under the same banner of "trauma." The child neglected into silence is not the same as the adult blindsided by disaster - and yet both deserve to be met with tools that fit their particular wounds.

This is why models that differentiate, rather than collapse, are so important. Among the most promising is the NeuroAffective Relational Model (NARM), developed specifically for developmental and relational trauma - the slow, cumulative impact of neglect, disconnection, and unmet needs.

The Trauma Training Institute (the sponsor of today’s newsletter!) has become a hub for this work, offering NARM training to therapists, coaches, and educators. What makes NARM distinctive is not only its clinical precision, but its attention to the therapeutic relationship itself. Research highlights three crucial aspects:

- Designed for developmental trauma - Unlike shock-trauma frameworks, NARM addresses attachment wounds and identity struggles.

- Protective for therapists as well as clients - Qualitative research in the UK and Ireland shows that NARM helps clinicians create safe therapeutic containers, reducing the risk of re-traumatisation.

- Sustaining the practitioner - Studies emphasise how NARM supports boundaries, prevents compassion fatigue, and reduces burnout.

The Trauma Training Institute’s courses range from weekend introductions to full professional training, based in London but designed to bridge academic rigour with day-to-day applicability. For practitioners, the appeal is clear: an approach that respects the complexity of trauma while offering a precise, relational map for navigating it.

And even for those outside the consulting room, the message is worth carrying: not all wounds are alike, and neither are the pathways to healing.

Keeping the Word Sharp

Trauma began as a word for wounds you could see: the gash of a spear, the fracture of bone. Over centuries it widened - to the shattered nerves of industrial accidents, the silent convulsions of shell-shocked soldiers, the haunted nights of Holocaust survivors, the activism of veterans and feminists demanding recognition. Today, it is everywhere: in diagnostic manuals, in political speeches, in Instagram captions.

That breadth has given us language for pain once unspeakable. But it has also blurred the edges. Trauma cannot remain a catch-all. A child's quiet shame is not the same as a soldier's battlefield flashback. A broken attachment is not identical to a car crash. Precision is not pedantry; it is compassion made practical.

For therapists, for researchers, for anyone trying to make sense of suffering, the task is clear: to name well, to listen carefully, to resist the temptation to flatten every hurt into the same word. For the rest of us, it is a reminder that words carry weight. Trauma is not just a term - it is a way of witnessing, of honouring wounds seen and unseen.

The challenge ahead is to let the word retain its force without erasing its nuance. To keep it sharp, not shallow. To ensure that when we say "trauma," we mean something real, something particular, something that deserves more than cliché.

Because in the end, language is also a wound, or a salve. And how we speak of trauma will shape not just how we understand pain - but how we heal from it.