How One Book Changed Who We Think We Are 📚

Are you experiencing ADHD symptoms? Do you feel like you might have BPD? Or perhaps you had Aspergers but now you’re not so sure?

The language around mental health is everywhere. In particular, the language around diagnosis. With the rise of the internet came lots of things: memes, flame wars, butler-based search engines. All good things. But something that also came with the internet age was an explosion in ways to define who we are: by how sick, or damaged, or abnormal we are, or believe to be.

The internet age has brought with it a shift in how we define ourselves. Sure there are still some of the older, less fashionable ideas: I’m sporty, I’m a Leo, I like football. But alongside those identifying features are things more acutely derived from medical textbooks: I’m bipolar, I have social anxiety, I probably suffer from major depressive disorder and so on. But where do they come from? And more importantly, why does it matter?

In this week’s Brink, I’m going to be taking you on a whistle-stop tour of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Illnesses, or DSM to its friends. This book has systematically changed the world as we know it. But that change has raised questions, lots of questions. Questions like: how are disorders actually devised? And “what happens when you keep lowering the barrier of what a disorder looks like?”

Questions I’m going to answer for you below. As Sigmund Freud always said, LFG.

A brief history of the DSM 🧐

If you want to understand mental health today, you need to understand the DSM. The book is at its simplest, a giant list of all the psychiatric disorders that psychiatrists believe exist (currently). More on why I’ve put parenthesis on “currently” later.

It started out in 1952, and its 130 pages were designed to help standardise how we diagnose the unwell. Before the DSM, across America - where the book comes from - psychiatrists had no way of comparing what they saw in patients with what other psychiatrists saw. While one doctor might describe a patient as ‘melancholic’, another might call them ‘depressive’. So the DSM was born to solve that.

Now, it’s important to point out that classifying mental illness has been going on since the early 1800s, it’s just that no classification system grew to have quite the sway over society as the DSM has. A great essay on the history of diagnosis can be found here.

Once the DSM was released, the idea was that every psychiatrist in America would use it to ascertain what was wrong with you. You describe your symptoms and the doc will try and match them to what’s in the book.

What happens if your symptoms don’t fit neatly into one category? You are given the label ‘comorbid’, i.e. you have more than one disorder. Simple, you might think. But things didn’t go all that well, and a decade later, the DSM had an egg on its diagnostic face.

Just say “thud”

After the second edition of the DSM came out in 1968, people were unsure about how accurate the DSM was. That’s because the way in which things were added wasn’t exactly scientific. Essentially, a collection of psychiatrists would sit together, describe the symptoms they saw, and then name the “constellation” of symptoms.

Once they had enough, job done. While that might sound glib, that was really how they came up with this stuff. There was language before the DSM, but the DSM set it in stone, sort of.

One psychiatrist wanted to test this theory out. Between 1969 and 1972, Professor David Rosenhan, a psychiatrist at Stanford University, sent eight pseudo-patients to 12 psychiatric hospitals without revealing this to the staff. None of the pseudo-patients had any symptoms or history of mental disorders.

Their instructions were simple:

- Book an appointment at the hospital, and when interviewed, mention they had been hearing unfamiliar, often unclear voices which seemed to come from someone of their own sex and which seemed to say “empty,” “hollow,” and “thud”.

- Once admitted, behave as you would normally.

All 8 patients followed these orders, including Rosenhan, and all were admitted to hospital. What happened next stunned not only Rosenhan, but the wider psychiatric community. Despite explaining the patients were fine, they were all given varying diagnoses, and all were given powerful psychiatric drugs.

Rosenhan himself spent two months in hospital. All participants realised that in order for them to get out they had to admit they were ill while saying they were getting better. This sent ripples throughout psychiatry.

The problem was that while the DSM had helped standardise the language of diagnosis, there was no accurate way of knowing if someone had a disorder and what disorder they had. So a solution was found: to write a new DSM that attempted to correct the bias that crept into diagnosis. Say hello to DSM-III.

Out with the old, in with the new ↩️

Part of the shift in the DSM was throwing out labels and finding new, more precise ones. In the DSM-II, homosexuality was listed as a mental disease, and was listed in the same category as paedophilia. Other things like ‘hysteria’ , a gendered form of dysfunction aimed at women, clung on.

Homosexuality was removed only after a vote by members of the American Psychiatric Association - not because there was new scientific evidence, but because of a shift in society’s perception of a broader sexual spectrum. Wait, hang on? Two questions: a) who on earth thought homosexuality was an illness and b) why was it removed again?

- Answer to question a) oh it’s complicated

- Answer to question b) a vote was cast and 5,854 psychiatrists said it should go, but 3,810 wanted it kept in.

By now probably what you’re starting to see is that the book wasn’t perfect. Far from it. The ‘science’ part was really more a discussion and based on what psychiatrists could observe in their own hospitals.

The idea with the third version was to remove any ambiguity in the definitions, and create more specific criteria for what made a person depressed, versus bi-polar. Did it work? Hmm… not really.

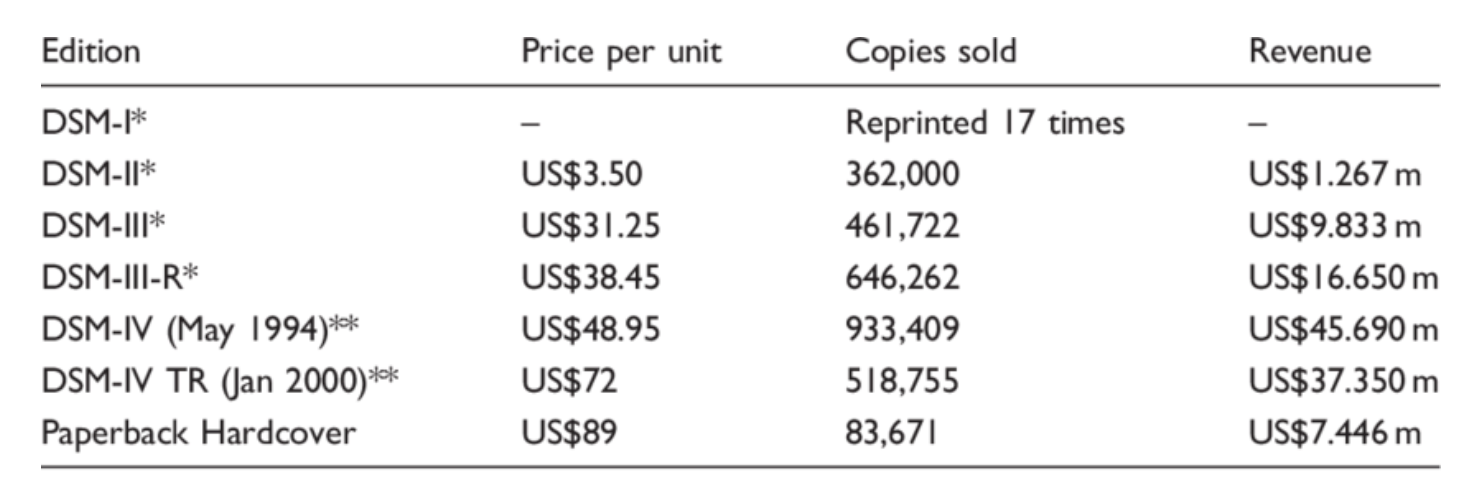

According to one study, when psychiatrists were asked whether they thought psychiatric diagnosis - based on the DSM - was now reliable, 86% said it wasn’t. But that didn’t stop the DSM-III from flying off the shelves. When it was released in 1980, Demand for it was so high, the publisher took six months to catch up on orders.

It spread from America to the UK, Australia, Canada, India and elsewhere. Psychiatrists across the world were now being taught directly from the DSM how to spot disorders. This book gave birth to 80 new disorders: from PTSD, to ‘major’ depression to social phobia and borderline personality disorder.

As a result, an “epidemic” of mental health began to emerge during the 1980s and 90s. In nationwide surveys in America, it found 50% of respondents were suffering from illnesses now defined by the DSM-III.

It was during DSM-III’s reign that insurance companies became increasingly interested in the manual. Thanks to all this lovely new language, people were drawn to these new terms to define what was happening to them.

But in order for them to get the help they needed, they needed a formal diagnosis. Insurance companies insisted a diagnosis is needed for a payout to ensue. Oh and pharmaceutical companies were very interested in the DSM-III’s rapid rise. The explosion of disorders meant a whole new marketplace for medication that essentially hadn’t existed before.

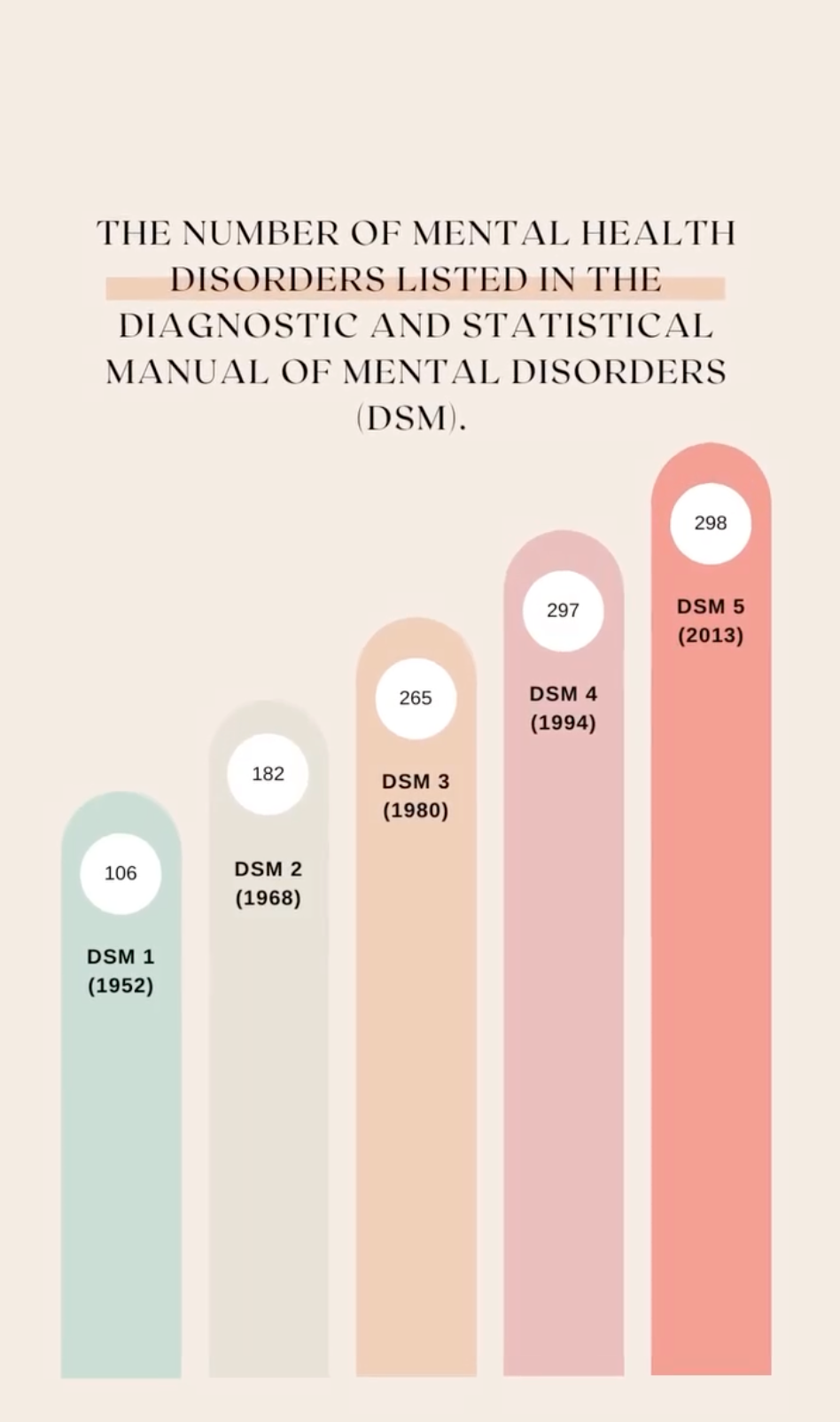

By the time the DSM-4 came out in 1994, millions of Americans - and now others across the world - were sick and in need of treatment. The number of mental conditions had risen from 106 in 1952 to 297. There were a lot more sick people it turned out, that needed a lot more treatment.

The 1990s set the tone for what was to come. An explosion in discussions around mental health spread across the sofas of chat shows of America and beyond. Oprah Winfrey was instrumental in bringing the conversation out of hospitals and into living rooms. And sales boomed.

The DSM has consistently sat in the best-sellers list for years. But by the time the DSM 5 came out in 2013, the number of disorders was now touching 300. What had changed?

For many professionals, it was simple: the barrier to being ‘disordered’ had been lowered as time went on to such an extent, that it was beginning to pathologise what were totally normal experiences.

A case in point: why were there 106 illnesses in 1952, but 300 in 2013? Had science caught up? Hmm… not really. Despite the early assertions that these orders had biological markers - i.e. you could measure them through blood and brain scans, the evidence never materialised.

Sure, we can see something is not quite right, but is that something bipolar, schizophrenia, or borderline personality? We’ve never been able to tell and our brains do not map with the diagnoses now spreading.

Why were we going so wrong? Turns out it wasn’t us, but the yardstick we were measuring ourselves against that was changing.

Let me give you an example.

Age-old problem 👴

In March 2011 a group of scientists decided to study 1 million school children in Canada. They were interested in the mental health diagnoses being dished out to kids and what might be the underlying causes.

So they took a million kids, between the ages of 6-12, and looked for children that had been diagnosed with ADHD. They wanted to understand were there any common causes to what was increasing the number of diagnoses in the study group. Do you know what they found? The single biggest contributor to whether a child would have ADHD or not was the month they were born.

For boys born in January, 5.7% were likely to be diagnosed with ADHD. In December, it was 30%. It’s worse in girls. December girls were 70% more likely to be diagnosed with ADHD than those born in January.

Now, if you’ve been to school, you’ll know that in one academic year, children can be as much as a full year older than others, it all depends on when you were born. In Canada, the school cut off is January to December, in the UK it’s September to August. An 11-month difference in kids is huge in terms of emotional and psychological development.

The younger children were being diagnosed as having ADHD because, well, they were younger, not because they were deficient.

When the DSM 5 came out, it had lowered that barrier again. To such an extent a petition was written - you can see it here - and had been signed by 50 organisations worldwide including the British Psychological Society, and the American Counselling Association calling for a re-write.

This is what they were most concerned about:

“The proposal to lower diagnostic thresholds is scientifically premature and holds numerous risks. Diagnostic sensitivity is particularly important given the established limitations and side-effects of popular antipsychotic medications. Increasing the number of people who qualify for a diagnosis may lead to excessive medicalization and stigmatization of transitive, even normative distress. As suggested by the Chair of DSM-IV Task Force Allen Frances (2010), among others, the lowering of diagnostic thresholds poses the epidemiological risk of triggering false-positive epidemics.”

In layman’s terms, when you label everything as disordered, you rule out what is for the most part, normal.

Everybody hurts, sometimes 😔

Now, I could go on and on and on and on. I haven’t even touched on the influence pharmaceutical companies have had over the book - and suffering in general.

But hopefully what I have shown you in this potted history of this book is that the ideas behind it are not scientific in the way we understand illnesses of other kinds. Instead, it is deeply driven by culture, society and what we define as normal. It is contested, not concrete.

Dr. Robert Spitzer, the father of the modern DSM, said it himself in an interview. In a quest to help people, we have over pathologised huge swathes of the human experience, calling for it to be medicalised rather than understood.

It’s important to note by sharing this history I’m in no way denying the experiences of people with diagnoses. Far from it. The way we feel is the way we feel, and if a label can help us to get the help we need, who is anyone to deny them that support?

Instead, I want to end this newsletter with an idea borrowed from philosopher Ian Hacking that can help clarify the point I’m trying to make. For Hacking, labels are not created equally.

Labelling people is very different from labelling animals, or buildings or diseases. Diseases don’t care what you call them. The opposite is true of people. When we label people it changes how we experience ourselves.

Take multiple personality disorder, or MPD. Between 1972 and 1986, the number of cases of patients with multiple personalities exploded from a few dozen to an estimated six thousand. Whatever one’s thoughts about the reality of these diagnoses, reckoned Hacking, everyone could agree that, in 1955, no such diagnosis existed.

By 1986, though, multiple personality disorder was not only a recognized psychiatric label; it was also sanctioned by academics, popular books, talk shows, and, most important, the experiences of people with multiple personalities.

Hacking referred to this process, in which naming creates the thing named—and in which the meaning of names can be affected, in turn, by the name bearers—as “dynamic nominalism.” That is when we give someone a label, it changes them, how they behave, and how people seem them. For better and for worse.

The history of the DSM, and our obsession with self-diagnosing ourselves is ultimately a quest for understanding. But along the way, the quest for understanding has brought up challenging ideas around the nature of understanding itself.

In our thirst to know more, might we be trading experience for a codified, quantified, but ultimately flawed set of criteria that might leave us feeling as alienated as we did in the beginning?

Things we learned this week 🤓

- 😱 At last! The gendered brain is finally dead - all eyes turn to culture and society now.

- 🌼 Fastest way to improve self-esteem? 1 week off social media.

- 🤖 Teens more likely to display ADHD symptoms in chaotic households

- 🧠 More evidence contributing to the idea that what we eat affects how we feel.

Just a list of proper mental health services I always recommend 💡

Instead of my usual news roundup, here is a list of excellent mental health services that are vetted and regulated that I share with the therapists I teach:

- 💓 Hubofhope - A brilliant resource. Simply put in your postcode and it lists all the mental health services in your local area.

- 📝 Samaritans Directory - the Samaritans, so often overlooked for the work they do, has a directory of organisations that specialise in different forms of distress. From abuse to sexual identity, this is a great place to start if you’re looking for specific forms of help.

- 👨👨👦👦 Peer Support Groups - good relationships are one of the quickest ways to improving wellbeing. Rethink Mental Illness has a database of peer support groups across the UK.

I love you all. 💋