How to flourish when the world is going to sh*t 💩

Oh it’s gloomy out there guys. Regardless of your political views, open your favourite news app and you’re inundated with all the bad things in the world. Whether it’s climate change, poo in the rivers, wars in the Middle East, the refugee crisis, the rise and rise of despots and dictators, the erosion of human rights. I could go on, but then you’d be so bummed out, you wouldn’t keep reading. But you get the point.

It can feel tough to feel good right now. But like with so many things in life, we must turn to that tiny, grey/pink part of our brains that deals with perspective. Which is where the idea of flourishing comes in.

The psychological concept that focuses on how we feel about the world around us - and how it connects to things like our sense of contentment can still thrive when the world looks like it’s going to shi*t.

So in this week’s Brink, I’m going to wade into the warm waters of flourishing and show how when we tear ourselves away from all the bad stuff that’s happening in the world, there’s still room for something more meaningful.

Are you flourishing right now? 🤔

What am I banging on about when I say ‘flourishing’? It’s an idea spoken about a lot in academic circles, but not so much IRL.

In a nutshell, it’s, “a state in which all aspects of a person’s life are good,” says Brendan Case, the associate director for research at Harvard’s Human Flourishing Program.

The university has been studying the idea of flourishing since 2016, by attempting to take this philosophical idea of “doing well” and applying good old fashioned statistical rigour to turn it into something more coherent.

The Program defined six domains that contribute to overall flourishing:

- Happiness and life satisfaction

- Mental and physical health

- Meaning and purpose

- Character and virtue

- Close social relationships

- Financial and material stability

In essence, flourishing is the idea of feeling good combined with functioning well. It’s those periods where we have a strong sense of meaning, mastery and mattering to others.

That third part is important, and what helps distinguish flourishing from the more narrow version we might see elsewhere.

I think we’re alone now 🥺

Hyper Individualism, or rather, capitalism’s very narrow definition of being an individual is the idea of doing what’s right for you, even if it harms those around you.

Think of it as the soul’s equivalent of eating junk food. It feels wonderful in the moment, but do it for long enough and the effects start to get harder to shift.

Last year, America’s Surgeon General Vivek Murthy sounded the alarm about what he called “the public health crisis of loneliness, isolation, and lack of connection in our country.” In essence what happens when we’re all out there, just individualising on our own.

The Department of Health and Human Services even released a surprisingly frank exposition of America’s social problems, titled “Our Epidemic of Loneliness and Isolation.” Social networks are getting smaller. Time spent alone is rising.

Three in ten households consist of one person. Only 30 percent of Americans think that they can reliably trust one another. And only 16 percent of Americans feel strongly attached to their local community.

The number of men with no close friends has increased fivefold since 1990. Suicides have increased in the United States since the end of the twentieth century, as have deaths of despair: the collective term for people dying by suicide, drug and alcohol poisoning, and chronic liver disease.

In 2016, Europe was found to be the most suicidal region in the world by gross rate. Average life expectancy has begun to decline. Flourishing is the opposite of this singular pursuit of happiness. It’s a collective pursuit. You do it with others.

What happens when you engage more in the world around you? Well, you feel a lot better.

The Global Compassion Coalition, a collective of academics and policy experts have done extensive research on how an active social life helps us live longer, feel better, and improve the environments around them. But to go back to flourishing more specifically, it’s an idea that can be more clearly understood when we look at its less glamorous counterpart: languishing.

Down in the dumps 😞

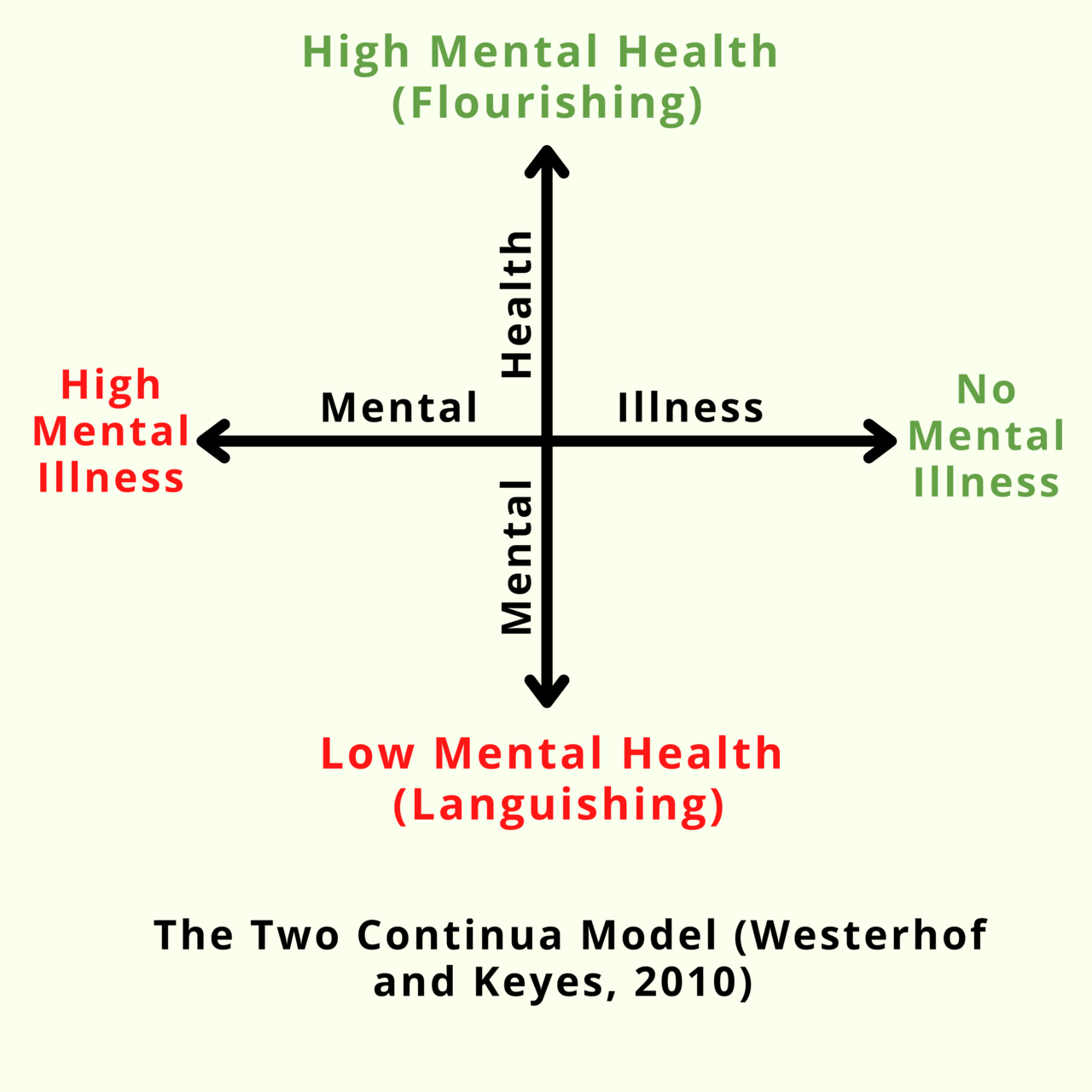

Languishing is the neglected middle child of mental health. It’s the void between depression and flourishing, marked by the absence of feeling good.

It flies just below the radar of being mentally ill, but robs you of the chance to function at your best. The term was coined by a sociologist named Corey Keyes, who was struck that many people in his study groups seemed to be stuck somewhere between ok and not ok.

His research suggested that the people most likely to experience major depression and anxiety disorders in the next decade aren’t the ones with those symptoms today. They’re the people who are languishing right now.

How do you know you’re languishing? It’s that gentle slide into indifference. You might find you’re spending more time alone, social relationships feel messier and harder to engage with. When someone asks how you’re doing, it’s a quick “fine” followed by a thunderous silence.

Now, there’s nothing wrong with languishing. I think it’s an important part of the human experience to know and be in periods of feeling a bit “meh”. See toxic positivity for more on that. But when we stare at all the terrible things in the world, that feeling of powerlessness can bring on a strong sense of languishing.

It can feel like the world is moving in the wrong direction. It can feel like powerful forces are slowly pulling the rug from under our feet and all is lost. I think inside the idea of flourishing is a response to that. A collective response that says, “not on my watch, pal.”

Turning away from the news for a second, and towards the world immediately around us can bring back a sense of agency: a belief that we can and do have an impact on the world around us.

Keyes identified five areas where we can see that impact:

- People who flourish help others. Whether through volunteering or homing in on your life’s purpose, Keyes recommends finding ways to make a small improvement in the world.

- People who flourish embrace learning. Acquiring new knowledge not only benefits your brain, but also “when we’re learning,” Keyes says, “we are opening ourselves up to growing and becoming better people.”

- People who flourish are spiritual. We don’t necessarily need to adhere to a specific religion to flourish, but Keyes says some acceptance of the existential — the “beautiful mystery” that is life—is helpful to thrive. “When you start embracing this, you start to feel comfortable in a world where there’s a long lineage,” he says. “You’re just part of a great chain of life.”

- People who flourish play. By that he means spending time doing something rather than passively receiving something, like TV or social media.

These ideas tap into something deeper in all of us: a drive to find each other when the chips are down.

Finding hope in a hopeless place 🙏

Are you familiar with the story of Ernest Shackleton’s heroic attempt to save his crew from certain death in Antarctica? It’s famous because Ernest and a group of double hard men rowed 700 miles in the Southern Ocean to save the rest of his crew from certain death.

What’s less famous is what happened to the men he left behind. The 22 men left on Elephant Island spent 128 days not having any idea of whether they will survive or be found. Do you know what they did to cope?

They put on plays for each other. They laughed together, they went on moonlit walks together. They found meaning in a meaningless place. And they survived. They flourished in the ways the Harvard study spoke about earlier.

I think about that story a lot when looking at the news at the moment. In the face of oblivion and uncertainty and awful people on the telly, we need to find the things that give our lives meaning. We need to find our equivalent of the plays and the moonlit walks those men found on that god-forsaken island they were marooned on.

What is that for us? Well, that’s for you to decide. But for me, it’s about helping people that I love, helping people that ask for help - I’m building a company that does exactly that - and trying as much as I can to be a positive contributor to my noisy corner of north London. And of course, write this newsletter. Yours might be completely different.

Before I go, I want to share one more story with you, which I think is useful when thinking about the end of the world and how we can flourish under the shittiest of circumstances.

Over in Georgia, in Eastern Europe or West Asia depending on who you ask, an archaeological dig turned up a jaw bone. It was a very old jaw bone, believed to be more than two million years old. It was human. Or rather, a variety of humans that no longer exists.

What was so special about this mandible? It was toothless. All the teeth had fallen out. But the owner, researchers believe, lived a very long time without any teeth. He was an old man, so his ability to capture and eat food would have been limited. The conclusion?

Someone fed him. For years.

Yep, two million years ago, our ancestors, knowing nothing, and understanding even less, were still able to care for one another. In a world full of hurricanes, and volcanoes and animals more than happy to eat them, this group of early humans knew how to find meaning in a world that made no sense to them. That, I believe, is how to live in a world that makes us feel like nothing matters.

Be kind. Be compassionate. Love your neighbour. Don’t be a dick. Flourish together, not apart.

Things we learned this week 🤓

- 🧑🎨 Want to be more creative? Sadness and fear may be the answer.

- ❤️🩹 There’s a strange link between religious beliefs and sexual satisfaction.

- 👨👩👧👦 The best protection from depression? A social safety net.

- 🍔 The faster your internet speeds, the more likely you are to be obese.

Just a list of proper mental health services I always recommend 💡

Here is a list of excellent mental health services that are vetted and regulated that I share with the therapists I teach:

- 👨👨👦👦 Peer Support Groups - good relationships are one of the quickest ways to improve wellbeing. Rethink Mental Illness has a database of peer support groups across the UK.

- 📝 Samaritans Directory - the Samaritans, so often overlooked for the work they do, has a directory of organisations that specialise in different forms of distress. From abuse to sexual identity, this is a great place to start if you’re looking for specific forms of help.

- 💓 Hubofhope - A brilliant resource. Simply put in your postcode and it lists all the mental health services in your local area.

I love you all. 💋