The myth of Myers-Briggs 🧞

If you’ve ever worked in a corporate environment, chances are you would have stumbled upon the Myers-Briggs test.

It’s a series of 93 questions, each one designed to prod and probe your personality. The goal? To put you, and everyone else into one of 16 different “types”. Those types are typically expressed in a series of four characters.

You might be an INFP, or an ENFP, or maybe one of the rare ones, an INFJ. The point? To create ”a powerful framework for building better relationships, driving positive change, harnessing innovation, and achieving excellence.”

That’s corporate speak for “we’ll tell you where you’re good and where you’re bad and how you can improve”. Pretty harmless, you might think. Could even be useful, right?

Well, it might be if those questions and those four-letter descriptions were actually based on anything whatsoever. Yep, the Myers-Briggs test is at best, totally meaningless and at worst, a way of segregating a workforce and homogenizing teams to act and behave the same.

And I’m going to tell you why.

A brief history of Myers-Briggs 📚

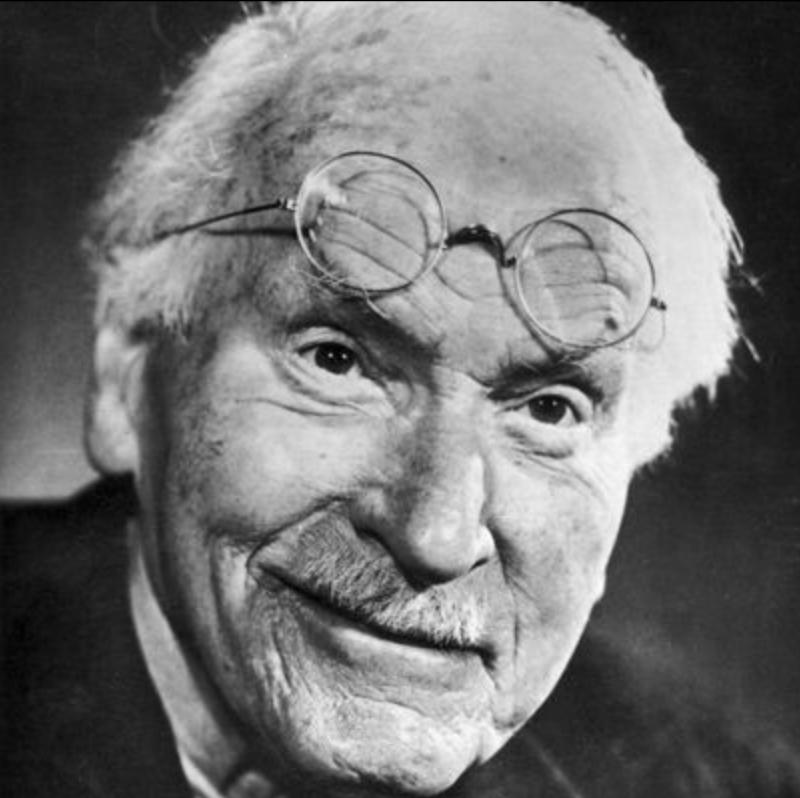

The test started life as a series of observations by Carl Jung, the famed psychoanalyst and peer of Sigmund Freud.

In his 1921 book, “Psychological Types”, Jung attempted to codify humans into distinct personas. He started out with the idea that people were broadly split into two groups: perceivers and judgers.

Then he went further. He thought some people were better at sensing and others intuiting. Then there were thinkers and feelers. Jung was on a role. By the time he’d finished postulating, he had come up with 16 rough archetypes. Jung based these assumptions on his own clients. He had no data or study to back it up.

But putting people into neat boxes was all the rage in the early twentieth century. Eugenics, the pseudo-scientific study of categorising human traits as superior and inferior had gained popularity in America and Europe. Theodore Roosevelt, John Maynard Keynes, and Adolf Hitler were all fans.

For Katharine Cook Briggs eugenics didn’t offer much. But Jung’s ideas however, had the secret sauce she was looking for.

A work of fiction 📖

Katharine Briggs was born into a wealthy family in Michigan in 1875. A bright student, Briggs earned a college degree in agriculture, and became a teacher in her twenties, occasionally dabbling in fiction writing.

It was while trying to make it as a writer, that Briggs created a framework for how to create better characters in her stories. She found if she broke people down into four categories:

- meditative types

- spontaneous types

- executive types

- sociable types

She could build personalities around those core identities with more success. But her fiction career wasn’t to be. After the birth of Isabel, who would become her only surviving daughter, she became fascinated by theories on how to raise and educate children.

Briggs had been trying to develop her own theory of personality based on her observations as a teacher and later on a parent. But with little success. She couldn’t quite make everyone fit inside the four categories she had created.

It was only when Isabel, then 26, began reading the work of Carl Jung that Katharine discovered a theory of personality had been developed by one of the twentieth century’s most important thinkers. She would go on to call him her “saviour”, “her maker” and “the author of her life”. Oh, and she wrote some erotic fiction about the psychoanalyst. That’s some serious fangirling.

But once the crush had subsided, Katharine, and her daughter Isabel, now Isabel Briggs Myes, would embark on a mission to change how we thought about personality forever.

A perfect storm 📖

First of all, the pair needed to work out three things:

- How to create tests

- How to do statistical analysis

- Find a bunch of people to test things on.

Luckily, Katharine Briggs and Isabel Myers had a family friend who had the solution to all three. He was called Edward Hay, and at the time he worked as an HR manager at a Philadelphia Bank. He was also in the process of starting his own consultancy to help companies “take advantage of improved personnel techniques” in his words.

Working Hay, Katharine, and Isabel, took Jung’s categories, gave them new names and created definitive identities that people could belong to. They were called Executive, the Caregiver, the Scientist and the Idealist. Meaning once you had carried out the survey you would be identified as that type.

The first version of these ideas was called the “Type Indicator”, and was first rolled out In 1942. With war waging in Europe and Asia, companies were looking for cheap, standardised tests to fit workers to the jobs that were right for them. It couldn’t have been a better time to release it.

From the end of World War II to the beginning of the arms race in the early 1950s, the test found its way into colleges, government bureaus, and pharmaceutical companies.

From Swarthmore, Katharine's alma mater; to her father’s longtime employer, the National Bureau of Standards, she had people completing her tests at the First National Bank of Boston, Bell Telephone, and even the Roane-Anderson Company — a subcontractor for atomic weapons her father introduced Isabel to through his contacts on the Manhattan Project. The pair never demurred on using their connections to further the cause.

Companies loved it. So much so, Isabel was invited into the boardrooms of some of America’s biggest companies to tell them what she thought the secret to being a successful executive must be. She told General Electric in the 1950s, an executive must "decide, he must be right, and he must convince key people of his rightness."

But in these early moments of success, the power that the mother and daughter wielded started to do strange things.

Only J's, no P's 🙅

Through testing, Isabel, who now took over the running of the test from her mother, believed she had understood what made good executives.

Back at GE, she decreed that only “J’s” or judging types in Myers-Briggs parlance could be good managers. When General Electric polled their managers, they only found 50% of them possessed the trait. The rest were “p’s” or perceptive types, who would prefer to analyse and consider more than one data point before acting.

Isabel had a solution: prescribe “personality drills” to the managers to help them become more like the types she believed would make better managers.

But that overreach was just the beginning. The Myers-Briggs personality test was about to redefine work in more ways than one.

A perfect answer to an imperfect problem. 🤷

The Myers-Briggs test crept into every facet of corporate life, and so did Isabel’s zeal for her own beliefs. Banks and hospitals would ask Isabel to evaluate their female workers — typists, nurses — to determine the relationship between personality type and a woman’s “excellence” on the job.

But the tests had been designed with men in mind, and Isabel found she had to tinker with the answer sheets to account for her belief that women were naturally less inclined to thinking than men.

But in her tinkering, she found everything she knew about performance was wrong. The best nurses, she was surprised to learn, were introverts. The best typists were intuitive, not sensing types, even though taking dictation had everything to do with sound and sight, with hands-on experience.

Isabel assumed the problem was the nurses and typists themselves: They had not answered honestly, she thought. So she tested them again, but their results changed. The flaw in the tests was suddenly revealed to Isabel: people weren’t fixed. They changed.

Jung himself admitted as much. The groups he created were a useful way of thinking about people, but "there is no such thing as a pure extrovert or a pure introvert. Such a man would be in the lunatic asylum."

"There's just no evidence behind it," says Adam Grant, an organizational psychologist at the University of Pennsylvania who's written about the shortcomings of the Myers-Briggs. "The characteristics measured by the test have almost no predictive power on how happy you'll be in a situation, how you'll perform at your job, or how happy you'll be in your marriage."

But while the evidence mounted against the survey, it had achieved a momentum that continues to this day. The survey continues to be taken by an estimated 2 million people per year, despite a litany of psychologists coming out against the test’s efficacy. McKinsey, Bain, Deloitte and Accenture continue to use a version of the test, despite research finding that as many as 50 percent of people arrive at a different result the second time they take a test, even if it's just five weeks later.

So why does it endure? Perhaps it’s in the way it makes people feel. The test, designed to find out people’s personality types, never discusses some of the less appealing aspects of our identity: laziness, anger, and jealousy.

The test is, actually quite flattering. It creates something called the Barnum effect: a common psychological phenomenon whereby individuals give high accuracy ratings to descriptions of their personality supposedly tailored specifically to them, but are in fact vague and general enough to apply to a wide range of people.

You typically find it in the worlds of astrology and fortune telling as a technique to impart generic information and make it specific to them.

So there you have it, an imperfect text for an imperfect problem, that weirdly, people seem to like.

Happy testing!

Things we learned this week 🤓

- 🤕 Romantic relationships, while great can often erode our sense of individuality and autonomy.

- 🚶♂️ Why walking helps us think.

- 👶 Attributing a child's emotions to "that's just what they're like" is a terrible idea.

- 🏋️ Researchers want psychiatrists to abandon the biomedical model of mental illness.

What you should do this week 📅

Become a member! This is the free version of The Brink, but there is a secret, extra special version that has things like:

- 🎤 Podcasts

- 📹 Video

- 🙋 AMAs - Ask me Anything and I’ll make a video an article for you to cut out and keep.

- 💆 Proper, researched ways of alleviating stress and anxiety.

It’s only $5 a month, or $50 for the year, which is 17% less than doing it monthly I’ve been told. What are you waiting for? Head here and click the "subscribe button".

I love you all. 💋