Why are we so terrible at looking after ourselves? 🤷

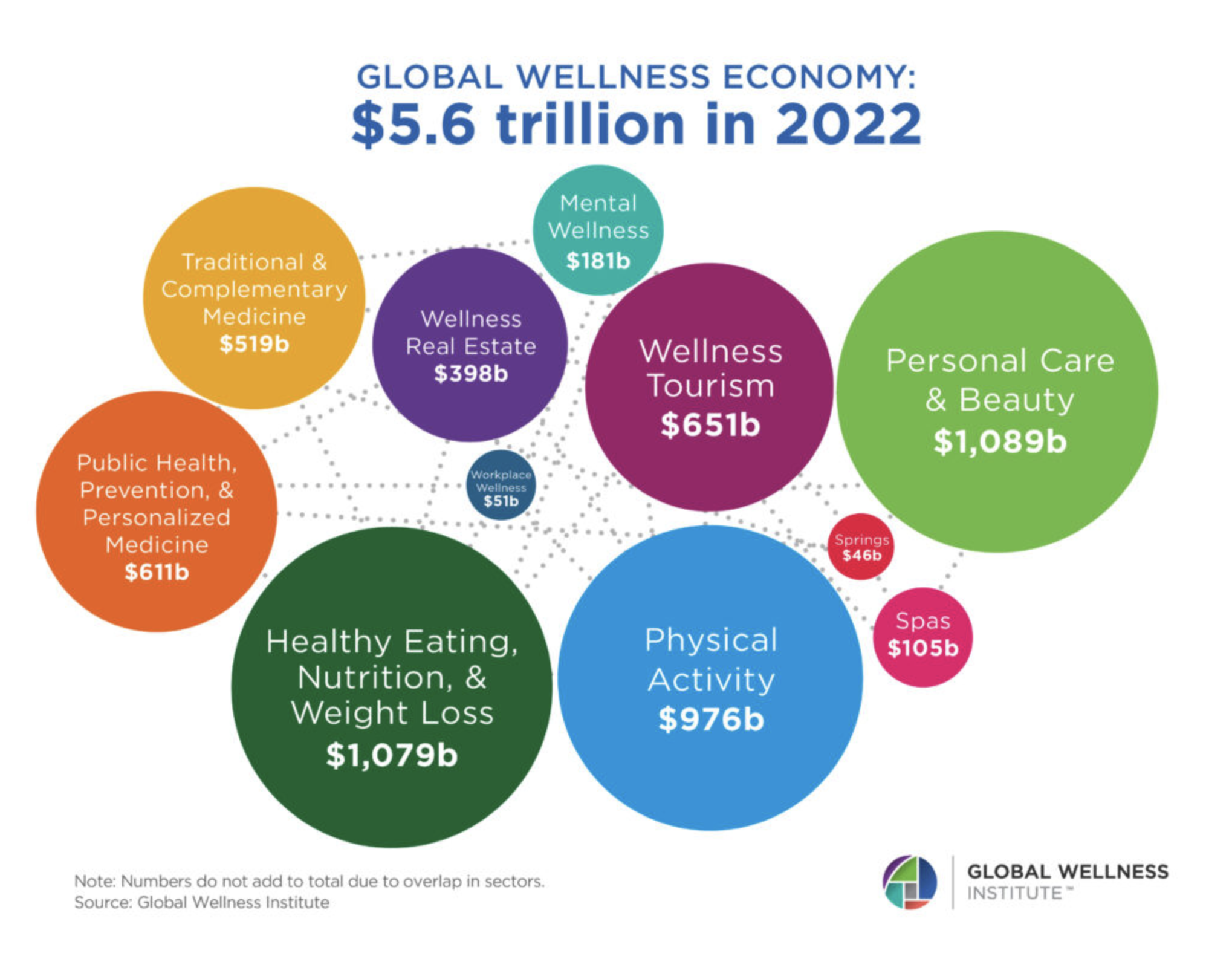

Self-care, wellness, focusing on you, being selfish. These have become synonymous with our times. The global wellness industry, which captures everything from traditional medicine, mental wellness, wellness tourism, personal care, healthy eating, spas, all the things designed to help us care for ourselves, is worth $5.6 trillion. Yes, I mean trillion.

So if a significant part of the world economy is dedicated to serving our basic need to care for ourselves, why do we find ourselves so consistently terrible at it?

Our sense of well-being, a measure of how good we think life is going, has been in decline since 2018, the mental and physical health of young people is also heading the wrong way, and burnout is on the rise globally.

In summary, despite a surge in wellness-related stuff, we don’t seem to be doing very well at keeping ourselves on an even keel. Why? Well, in this week’s Brink, I’m going to tell you.

TL:DR low compassion has nothing to do with access to products and services, and more to do with our core inner beliefs. Intrigued? Read on.

The Inner Critic 👹

Here’s a little exercise: when you’re doing an activity or a task, have you ever stopped and listened to the inner monologue going on inside your head? If you’re like me, that’s a silly question. Of course you do. The voices inside your head never seem to be quiet. Fun fact: some people have a condition where they do not have any internal monologue.

You’ll probably also tell me that the majority of the conversation inside your head will mostly be critical or negative. The voice will rush in to say you’re doing a bad job, or someone will think less of you, or worse, convince you that the mere act of trying is pointless.

This voice is why we’re so bad at looking after ourselves. The inner critic, a much-talked-about but little-understood concept, is the primary driver of why we can never take a break, leave that bad relationship or boss, or do something positive that might change our lives for the better.

Some of us may not even be aware of this critic, as it quietly, but persistently chastises you for existing. But it is there, and it does drive an awful lot of what could be called comfort-seeking behaviour.

This is a form of self-soothing: we can’t gain what we need from a person or relationship so we try to soothe that pain through other means. This can be anything from comfort eating, maintaining destructive relationships or behaviour patterns, alcohol, drugs, or anything that gives the feeling that we can quiet, sate, or soothe the pain we feel at the hands of the critic. See: the multi-trillion dollar wellness industry.

But here’s the kicker: the shame/sate dynamic doesn’t really go away, it just resets and will start again whenever there’s a new stressor. In essence, the wellness industry has got so big precisely because it doesn’t do a great job at breaking this chain, it just keeps it going.

But where does it come from? Well, like everything else, it starts in childhood.

Child Critique 🧒

First, it’s important to establish what we mean by the inner critic. In the therapy world, it’s described as something that “manifests as an internal voice characterised by self-judgement and a critical stance toward oneself. This voice shapes self-perception and contributes to feelings of inadequacy, anxiety, or depression.”

Essentially it’s an idea that there is a key part of us always on hand to give us a good kicking whenever possible. The good news is, we’re not born with it. The bad news is, we all take on a version of it as a result of our childhood.

Research suggests that people with these tendencies learnt them from frequent experiences growing up that contained judgement, ridicule, and a scarcity of positive regard. These experiences can come from anywhere, but they typically focus on one of these four:

- Parents

- Teachers

- Siblings

- Peers.

Parents sadly make up the lion’s share of critical experiences, and anyone growing up in a family that felt critical, controlling, demanding, abusive, or indifferent to the child will often develop a harsh inner critic. Essentially, we internalise those voices and make them our own. But why? Well, it has something to do with our survival.

Object Relations 🎾

When we’re born, our survival, quite literally, depends on our ability to fit in and belong to our family group. Our parents are our source of food, shelter, well-being and self-regard. As a result, our baby brains intensively record and then mirror back what they see as the family’s typical behaviour to help the child belong to the group.

Our brains also do not have any other frame of reference, so it records pretty much all that it sees. But as the child grows up, they will start to experience a misalignment with their parents. That is, there will be experiences where the child’s needs are not met, or don’t fit with the family narrative. This is very normal and can be corrected, helping the child resolve the problem and move on.

If however, that misalignment is left and allowed to grow, the child is faced with a conundrum: how do I work out why my parents do not meet my needs? On the one hand, we could blame our parents, and criticise them - this can most commonly be experienced as acting out or defiance. But this is a high-risk strategy: we are risking acceptance and our membership of the group to be treated better.

The other approach is to blame ourselves. The reason why our needs are not met is because we have done something wrong - that is, we take on the critique of our parents and make it our own. The impact of this is that it preserves the parent as ‘good’, but as a result, it makes us ‘bad’. This is why so often people find they can’t escape coercive relationships: they preserve the other as the good, loving object, and keep themselves as the bad, shameful object.

This is the crucible of the critical voice: an intense battle of survival, belonging and personal growth that takes place without anyone ever really noticing. But before we all grab our psychological pitchforks and start haranguing our parents, this critical voice plays a somewhat useful role.

Critical Protection 🙅♂️

When we think of critical voices, we might think them to be useless. But they have a role. Critical voices are trying to protect us from something it believes is more painful. That greater pain might be shame, rejection or humiliation.

So the critical voice says, “Hey, it’s either me sitting on your shoulder keeping you from harm, or it’s the judgement of everyone else around you.” This devil’s bargain is more often than not, why we continue to experience the critical voice. It keeps us from greater harm.

It does that by using historical experiences to fill in the blanks of what might happen next. Let’s take an example: you’re working late at work, way later than you intended to. The reason? If you don’t finish that thing bad things will happen. Those bad things will be a distorted replica of previous experiences where you’ve been made to feel bad, stupid, not professional, choose your poison here. So the critic leaps in to protect you from that worst thing.

But the challenge we all have, and why taking care of ourselves in a meaningful way can feel so elusive, is that we need to find a way of assessing whether we still live in the same world we did as a child. That is, are we still in a highly critical, judgemental space, or have we managed to find somewhere that feels safe enough?

If the answer is no, we still exist in an insecure world, we need to understand what we need to feel safe and exert as much energy as we can to establish it. If we do feel we are safe enough - I use ‘enough’ here as what feels safe to one of us might not feel safe to another - then we have an opportunity to work towards the idea of helping that critic have the day off.

The protective role of the critic can be slowly, and with time let go. In its place, we can hire a new voice that helps us understand that part of living will mean that we will experience rejection, shame and neglect, but that doesn't mean we are a bad person. We’re just a person trying to live.

Ultimately this will help us move beyond working 4,000 hours straight but then go and spend all our money on self care products to help prop up the unsustainable demands of the inner critic.

See you on the other side.

Things we learned this week 🤓

- 👩💼 Managers unconsciously tend to exploit the most loyal employees.

- 🏃 Mega analysis now doubly absolutely confirms: exercise can help treat depression.

- 📉 Why you should avoid reading the news.

- 😭 Why compliments make us feel the opposite.

If you would be so kind 🙏

I am terrible at marketing. Literally terrible. But I’m trying to get better, and I need your help!

If you enjoy my witterings, please do share with someone or subscribe, it really helps.

I love you all. 💋