How to (and definitely how not to) deal with the end of the world 🤯

These are tough times. Come to think of it, I said the same thing three years ago during the depths of Covid, when I first started writing about mental health. And look at us now! We fell out of the pandemic frying pan and into the existential fire of war and climate change. Typical.

But nonetheless, here we are, facing multiple threats to our lives: climate change, war, racism, hatred, AI, and politicians going on popular TV shows to buff up their tarnished image. Many people are rightly feeling that things are terrible. So what to do?

Well in this week’s Brink, I’m going to be exploring how to deal with all the chaos and uncertainty that seems to be everywhere, and how not to. I’m going to be lurking in the darker corners of the internet and the dustier parts of my INCREDIBLE BOOKSHELF to find both problems and solutions in equal measure. Oh, and there’s a great story about a 2 million-year-old jawbone at the end of it all. Ready? Lego.

The world is ending and it’s all your fault 😡

Earlier this week, I was sent this video and asked what I thought about it.

Holy Sh*t.

— AG 🔥 (@Yolo304741) November 14, 2023

THIS is a must watch! pic.twitter.com/yXKPX5VNbh

I don’t know who the person speaking on camera is, but the video has been watched 1.5 million times and shared by thousands. If you haven’t seen it, the speaker delivers a bit of a sermon on some of the things befalling us: a loss of purpose, the collapse of community, and of course the environment. But amongst those things were some other things too.

Things like, a shady elite seemed to be running things, we live in a matrix, and oh, trans people are not a grassroots movement, but in fact a government plant. Reason has left the building.

Holding back the world’s biggest eye roll for one second, I was curious. Why had this particular orator taken things that were largely true, and mixed them in with things that definitely were not?

Now I’m sure this person has their reasons, but one interpretation is this: the world is a chaotic, random, sometimes cruel, sometimes exciting place, that has order and meaning in some places, but also the complete absence of rhyme or reason. This idea gives us a massive headache.

One way of relieving that headache is by giving it an order, or an explanation as to what is going on. Even if it is far-fetched.

People need to feel they’re in control of their lives. Most of us, for example (me included), feel safer when we're the driver in the car rather than a passenger. The idea of being able to control our destiny is a powerful one.

Similarly, grand ideas or conspiracy theories can give us a sense of control and security. This is especially true when the alternative account feels threatening. Take global warming as an example. If global temperatures are rising catastrophically due to human activity, then I’ll have to make painful changes to my comfortable lifestyle. But if pundits and politicians assure me that global warming is a hoax, then I can maintain my current way of living. This kind of motivated reasoning is an important component of conspiracy theory beliefs. They help give us a sense of control, and they give us a clear understanding of who or what is making us feel bad.

But this is precisely the wrong way to deal with the threat of the end of the world. And I’m going to try and explain why.

Critical Reason Machines we are not 🤖

When reading a newspaper, or scrolling through a newsfeed, we are deluged with information on people, places, and ideas. The internet, being the caring sort of thing that it is, tends to serve us the things that are popular.

The most popular things on the internet (according to the algorithm’s own yardstick) are things that make us react and share. These things tend to be the things that make us angry, sad, etc.

So the internet shows us a sad, angry, frustrating world. This can often lead us to the conclusion that the world is a sad, angry, frustrating place, and you can do nothing to stop it. An easy solution to come to. But you are wrong.

The reason why we are wrong has something to do with our ability to think critically. If the world were going to hell in a handbasket, that would mean every single facet of our lives would be breaking down, and it might be. But if you’re reading this, you’re probably doing ok. But still! I feel bad, so the world must be bad, right? Well, kinda, but not really.

You see, we are not a species designed to think critically: that is to weigh up all factors and be able to make reasonable decisions. Don’t believe me? Try this.

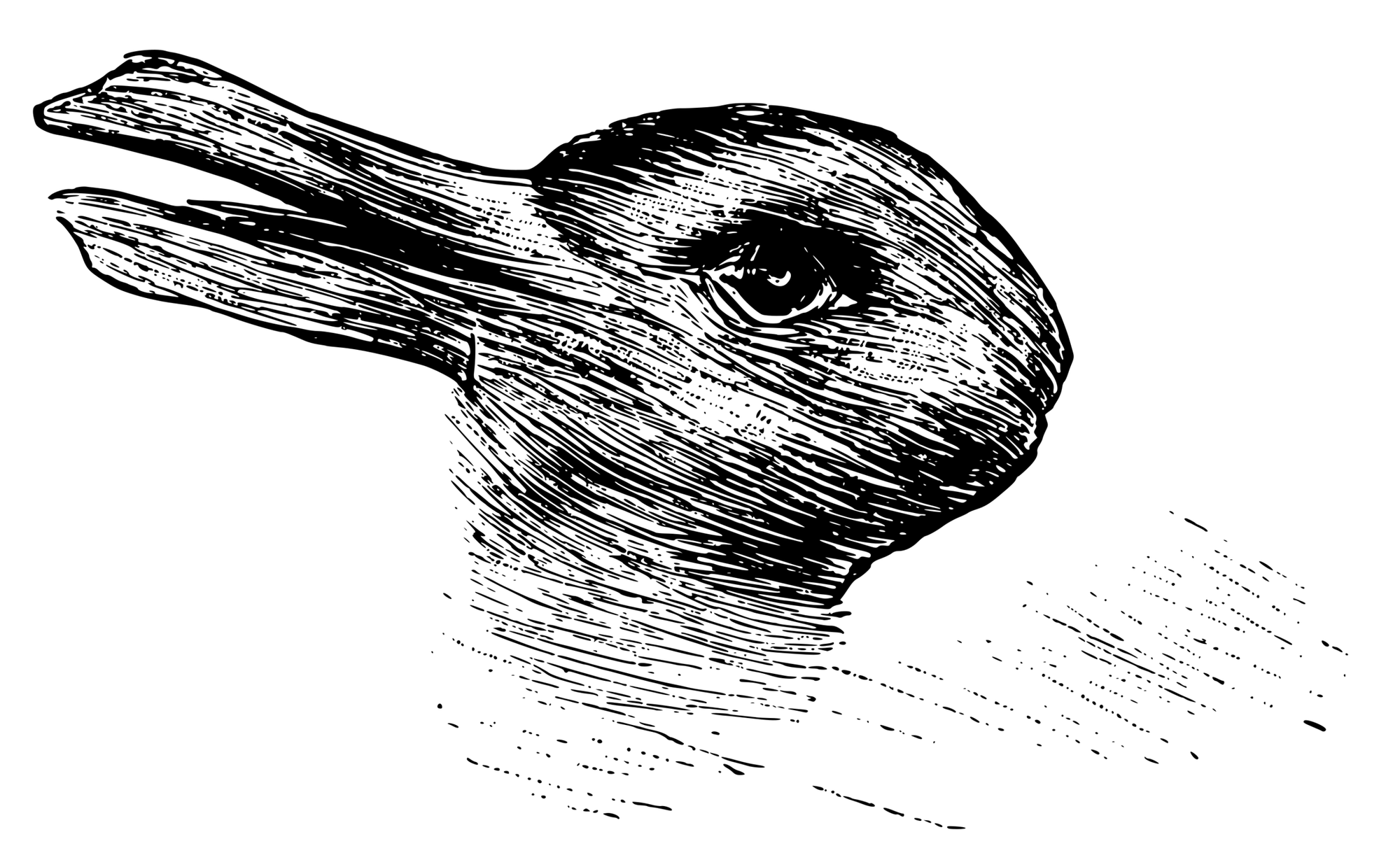

Is this a duck? Or a rabbit?

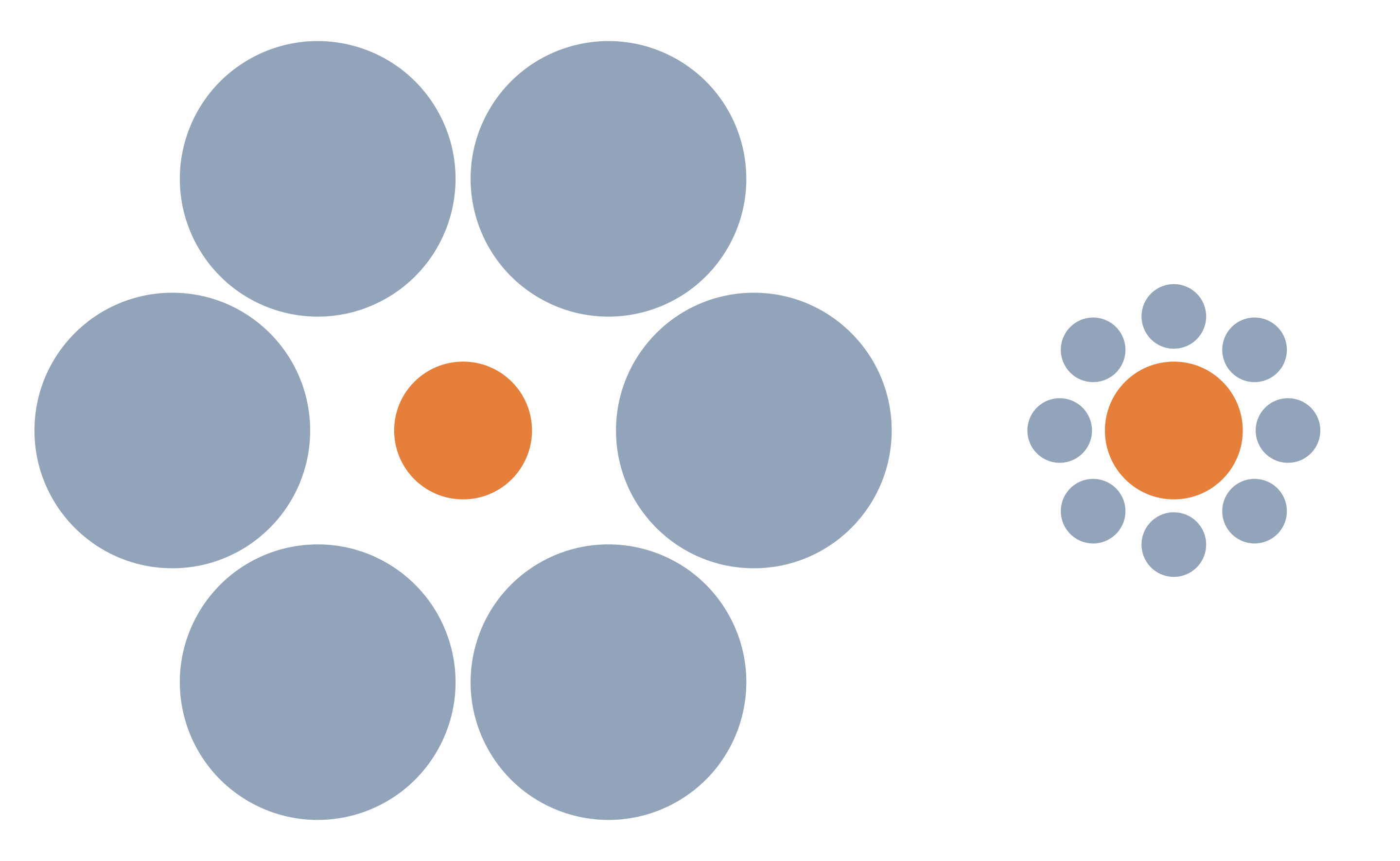

Or which of the two orange circles is bigger? The one on the left or the one on the right? Neither. They're both the same size.

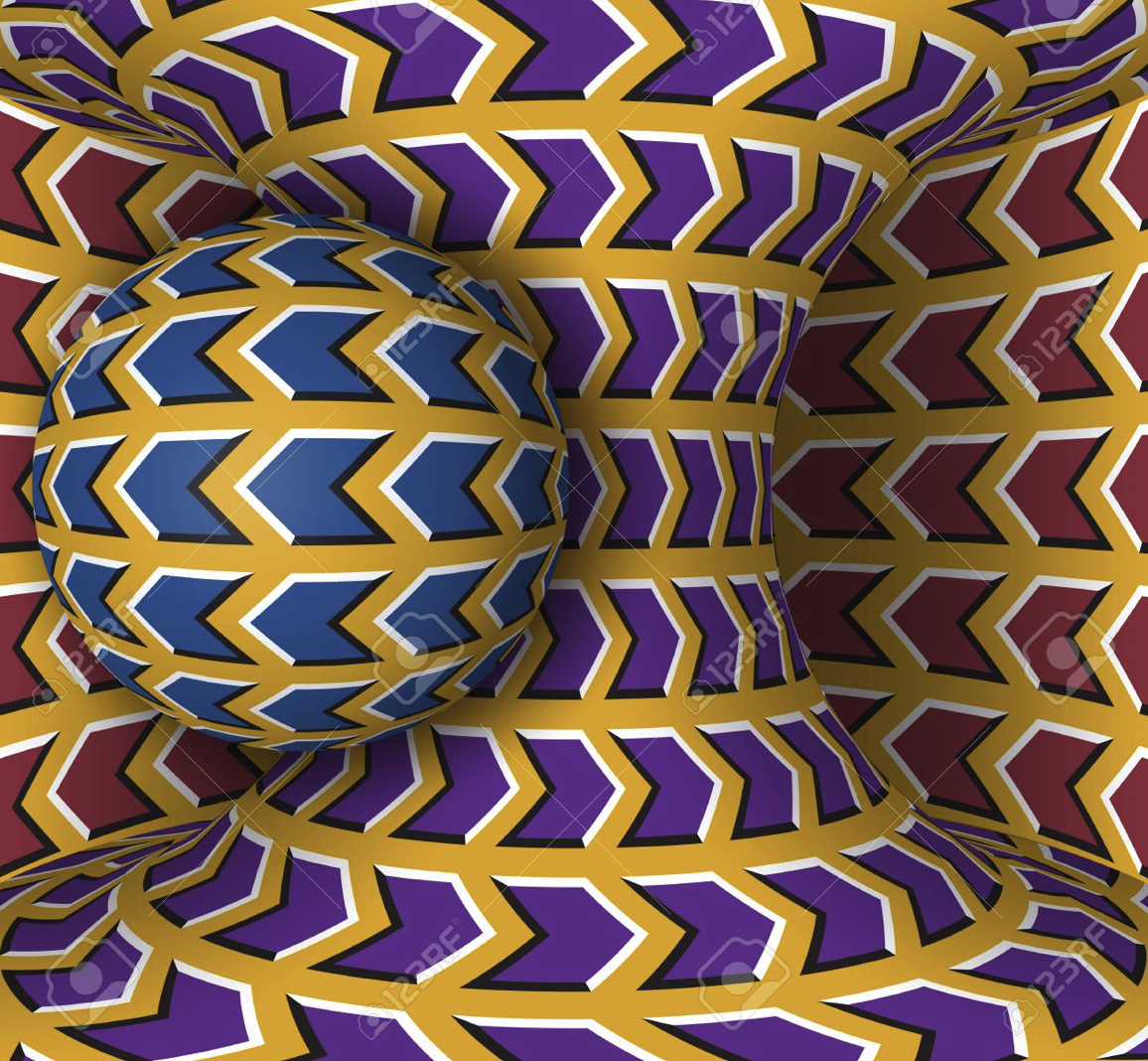

Which is rotating faster the sphere or the column in the centre? Neither, it's a still image, your brain is kindly animating it for you.

These are just silly optical illusions that trip us up. How the hell are we supposed to see true reality when it comes to things that actually matter in our lives? Well, for as long as we've been trying to grapple with reality, there has been an enemy sabotaging us at every turn.

That enemy is called a logical fallacy, and it is the essence of how not to see the world.

I correlate, therefore I am 🤓

Our world is full of logical fallacies. Let’s take an example. The correlation fallacy is probably the one we inadvertently bump into the most. It’s when we group things together and think they’re related - like the video I showed you earlier.

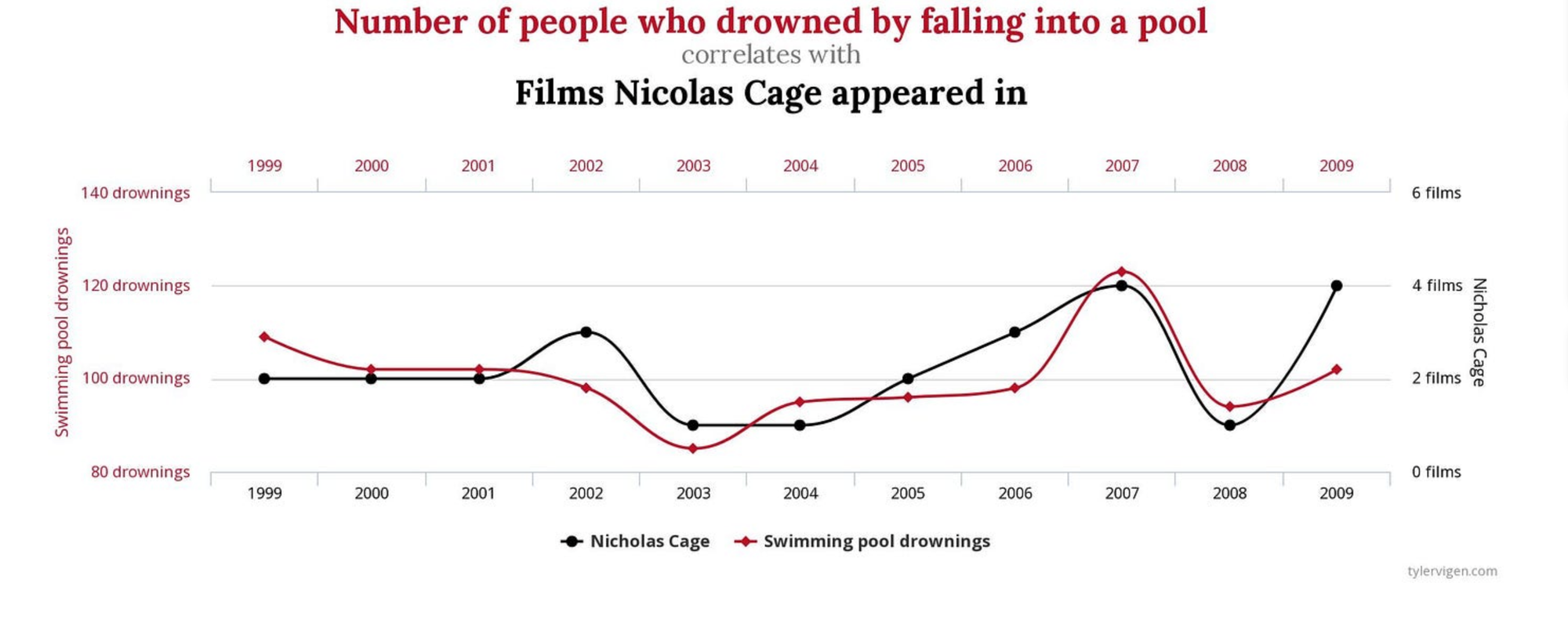

Correlation does not equal causation. If it did then we should be VERY worried about the below chart that tracks the correlation between the number of people who drowned by falling into swimming pools from 1999 onwards and the number of films around that time Nicolas Cage appeared. Is he to blame for all the drownings? He might be.

Then there’s the slippery slope fallacy. Let’s take an example. You’re having a coffee with someone and they suggest to you that your love of a bacon sandwich or smashed avocado on toast or oat milk is harming the planet. So they suggest thinking about giving it up.

Using the slippery slope fallacy you reply, “If we do that then what next? You’ll be telling me to give up my car, my love of long-haul holidays, my children, my home, breathing. Is that what you want!” all the while your lunch/coffee is splattered all over their face. It is possible to make a change to the status quo without the complete collapse of physical reality.

Let’s take the false dichotomy fallacy. This is a favourite of TV shows and pundits who love to present an A or B choice that isn't actually A or B. These include things like, well, save the rainforest or save the whales? Go on holiday or eke out your summer existence in a bog in Wales. Eat forty rashers a day or live on hopes and dreams for sustenance. It’s silly, but it’s powerful.

Other examples that you don’t have the time to read are:

- The argument from tradition - we should continue to do things because we’ve always done them.

- The argument from false authority - I visited Israel 10 years ago so I’m now an authority on the subject

- The argument from being oh so very reasonable and your opponent being oh so very silly.

This is how not to look at the world. Because when we look at the world in this way, we may get a little boost of confidence, security, or understanding, but ultimately the tsunami of chaos that is the world as it really is, washes that frail security away.

So then clever clogs, what to do about it all? To take a leaf out of Albert Camus’ book.

It takes Camus to tango 💃

Taking a turn back into the 20th century for a moment, a lot of answers to how I think we can face the litany of shit in front of us is to embrace an oft-forgotten idea called Absurdism.

First created by Albert Camus, a French Algerian philosopher, he rejected the core idea of existentialism. That is, there is no meaning in the universe which leads us to the inevitable unanswerable question, “what is life even for?”

Instead, Camus believed that the real problem is, we are things that crave meaning and purpose in a universe that is cruel and unpredictable and apparently completely apathetic to our needs. Oh don’t look at me like that, you choose to read this thing.

We are born, we grow up, we do the things we try to do, we die, and we have no idea what any of it means, apart from we spend most of our time feeling exasperated or annoyed at the world. In light of this, Camus argued, leaves us with three choices:

- Refuse to play the game. This could be either dropping out of society or sliding into full-on nihilism and falling into the logical fallacy trap. Please don’t do that.

- Put your faith into something that provides a type of meaning or way of being. This could be anything from believing in a deity, to SoulCycle to rolling a series of magic dice before making major life decisions. OR

- Absurdism - this is to recognise and accept that the world can make us feel mad, bad, and sad, and most of the time it will never behave the way we want it to, and that’s ok.

The only way to cope with it all, said Camus, is to stare into the randomness of it all, and embrace it by grabbing the things that make us feel human and alive and make our way through this wild storm holding on to the things that matter. Think I’m mad? Ok, give me a moment.

An island of madness 🤪

he story of Ernest Shackleton’s heroic attempt to save his crew from certain death in Antarctica is famous because of how he and a few of his men travelled 700 miles in a rowing boat in the Southern Ocean to save his men from certain death.

What’s less famous is what happened to the men he had left behind to go and find help. The 22 men left on Elephant Island spent 128 days not having any idea of whether they will survive or be found. Do you know what they did to cope? They put on plays for each other. They laughed together, they went on moonlit walks together. They found meaning in a meaningless place. And they survived.

I think about that story a lot when looking at the news at the moment. As Camus says, in the face of oblivion and uncertainty and awful people on the telly, we need to find the things that give our lives meaning. We need to find our equivalent of the plays and the moonlit walks those men found on that god-forsaken island they were marooned on.

What is that for us? Well, that’s for you to decide. But for me, it’s about helping people that I love, helping people that ask for help, and trying as much as I can to be a positive contributor to my noisy corner of north London. And of course, write this newsletter. Yours might be completely different.

But before you throw the book of white privilege at me, I want to share one more story with you, which I think is useful when thinking about the end of the world and how we can all be more compassionate to ourselves and each other.

Over in Georgia, in Eastern Europe or West Asia depending on who you ask, an archaeological dig turned up a jaw bone. It was a very old jaw bone, believed to be more than two million years old. It was human. Or rather, a variety of humans that no longer exists.

What was so special about this mandible? It was toothless. All the teeth had fallen out. But the owner, researchers believe, lived a very long time without any teeth. He was an old man, so his ability to capture and eat food would have been limited. The conclusion? Someone fed him. For years.

Yep, two million years ago, our ancestors, knowing nothing, and understanding even less, were still able to care for one another. In a world full of hurricanes, and volcanoes and animals more than happy to eat them, this group of early humans knew how to find meaning in a world that made no sense to them. That, I believe, is how to live in a world that makes us feel like nothing matters.

Be kind. Be compassionate. Love your neighbour. Don’t spend too much time on social media. Don’t be a dick.

Things we learned this week 🤓

- 🥰 Being good looking makes it easier to achieve social mobility

- 🫥 Being sexist makes you a bad parent.

- 🍔 Your personality type has connections with what types of food you eat.

- 💪 What doesn’t kill you makes you stronger? Apparently so, according to kids who endure trauma.

If you would be so kind 🙏

In light of this week’s newsletter, I’ve listed some of my favourite local charities, if you feel you want to make a difference.

- Raise your Hands - an amazing project that helps local, small charities continue the amazing work they do.

- Bankuet - A national scheme that helps local food banks stay fully stocked.

- Refugee Action - has helped refugees the world over find somewhere safe to live.

- Climate Coalition - A group of charities working to help mitigate climate change.

I love you all. 💋